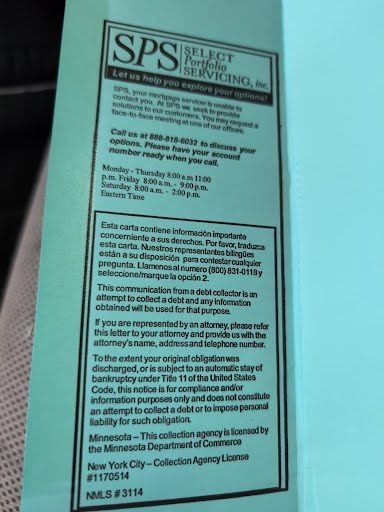

In the aftermath of a year already marred by violence and fear within the mortgage field services industry, the image of a brightly colored door hanger bearing the logo of Select Portfolio Servicing, Inc. should chill anyone who values safety, legality, and basic human decency. The notice—left on doors by Inspectors under orders from banks, mortgage servicers, or order mills—demands “property verification” from occupants and includes language that many consumer attorneys now argue runs afoul of the Fair Debt Collection Practices Act (FDCPA). To the untrained eye, it may seem like harmless paper. To those in the field, however, it represents a direct invitation to confrontation, liability, and, increasingly, violence. The time has come for the industry to return to the pre-COVID practice of drive-by inspections, where Inspectors document from the curb and leave residents in peace.

Before COVID-19, occupancy inspections were largely visual drive by inspections. Inspectors confirmed habitation through observable indicators—lights on, trash cans out, curtains drawn—without any face-to-face contact. HUD, the VA, the USDA, and even the GSEs never required door knocks or physical contact as a condition of compliance. The logic was simple: Inspectors are not debt collectors. They are independent contractors tasked with reporting property conditions, not initiating borrower communication. When the pandemic hit, servicers panicked. In the name of “verification,” they began requiring Inspectors to photograph the front door, knock, and even engage with occupants to confirm identity and phone numbers. What began as a temporary COVID-era safety measure quickly metastasized into a permanent expectation—one that now places workers directly in harm’s way.

The FDCPA makes it clear that any communication that could be construed as an attempt to collect a debt falls under its jurisdiction. Door hangers like the one from SPS are saturated with collection language—statements about debt validity, disclosures required for collection agencies, and contact information for disputing debt claims. Yet, the individuals distributing them are not licensed debt collectors. They are Inspectors operating under subcontracts, often through two or three layers of vendor management, earning as little as three to five dollars per inspection. By instructing these workers to leave such materials, servicers are effectively transforming them into unlicensed collection agents, exposing both themselves and their contractors to potential federal violations. Worse, they are doing so without offering insurance, training, or legal indemnity.

It would be naïve to think that the National Association of Mortgage Field Services—or whatever it calls itself now—will raise its voice against this encroaching disaster. After all, this is an industry whose leadership remained silent after one of its own was murdered. Instead of calling for improved safety standards or coordinated identification systems, it launched a podcast series celebrating profitability and workflow management. The silence of NAMFS, and by extension the silence of the large national firms it protects, has created the perfect vacuum into which laws are flagrantly violated.

This transformation has ethical implications beyond mere compliance. Inspectors are not equipped to deal with irate or frightened homeowners. Many of the people receiving these notices are already under immense stress—behind on payments, facing unemployment, or grappling with medical debt. A stranger knocking at the door and leaving a notice bearing the name of a mortgage servicer can easily escalate a volatile situation. The death of Field Service Technician Michael Dodge II should have been a clarion call for reform. Dodge’s murder while performing legitimate preservation work illuminated the deadly consequences of forcing labor into unpredictable environments. Requiring Inspectors to knock and engage with occupants only amplifies that danger. And now with ICE sending out private bounty hunters to perform nearly identical tasks, the reality is not if but when do the bodies begin piling up!

Ironically, the government agencies that oversee mortgage servicing have already abandoned most of their pandemic-era protocols. Under the Trump administration, nearly all temporary COVID mandates tied to the US government, including in-field verification, were rescinded. Federal guidance now explicitly favors non-intrusive inspection methods. Yet order mills continue to cling to the knock-and-hang model, driven not by necessity but by profit. Each “verified contact” can be billed at a higher rate to investors, and in an industry where margins are razor-thin, the temptation to monetize human risk has proven irresistible. What remains unspoken is that every dollar earned through this practice comes at the potential cost of a life.

Field Service Technicians and Inspectors occupy different but equally vulnerable positions within the mortgage field services hierarchy. Technicians handle the physical labor—board-ups, lock changes, debris removal—often at abandoned or condemned properties. Inspectors, on the other hand, are dispatched to verify occupancy and condition. Both groups are misclassified as independent contractors, both lack meaningful safety protocols, and both face escalating hostility from the public. The growing confusion between these roles—compounded by servicers treating Inspectors as quasi-collectors—has made every job more dangerous. Homeowners no longer distinguish between a preservation worker and a repossession agent. To them, every knock is a threat.

The SPS hanger in the photograph epitomizes this confusion. Its fine print references debt collection disclosures, New York City licensing, and consumer dispute rights—all hallmarks of an FDCPA notice. Yet, Inspectors have no training in debt collection law and no authority to discuss account balances. By distributing such documents, servicers are effectively deputizing untrained workers to perform a function they neither understand nor are legally allowed to conduct. If challenged in court, these hangers could be used as evidence of unlawful debt collection practices and worker misclassification. The legal exposure for both servicers and their contractors is staggering, but the human cost remains higher still.

The simplest, safest, and most compliant solution is also the oldest one: the drive-by inspection. No knock. No door hanger. No confrontation. Just observation, documentation, and submission. Technology now allows for geotagged photographs and real-time GPS verification, rendering the old-fashioned door knock obsolete. The government’s own servicing guidelines do not require it. Yet the industry persists, trapped in a mindset that equates visibility with value. They would rather risk a lawsuit—or another death—than lose a few dollars in billable contact attempts.

It is worth remembering that the mortgage field services industry exists because of government tolerance, not statutory entitlement. HUD, the VA, and the GSEs could easily impose uniform safety standards tomorrow, prohibiting door knocks and prohibitive contact. They could mandate that any borrower contact be handled by licensed mortgage servicers or verified third-party call centers. They could remind the industry that Inspectors are not collectors, that Field Service Technicians are not law enforcement, and that property preservation should never become a death sentence. Instead, regulators have allowed servicers to set their own rules—rules that reward aggression and punish caution.

For those who labor in the field, every new door hanger is a reminder of how expendable they have become. Inspectors are told to “make contact” but not to trespass, to “engage politely” but not to argue, to “get the photo” but not to get killed. It is an impossible calculus, one that forces workers to gamble with their safety for pennies on the dollar. Returning to drive-by inspections is not just a matter of compliance or convenience. It is a matter of survival. The paper hanging on that door is more than an FDCPA violation waiting to happen—it is a warning that the system itself has forgotten who does the work, who takes the risk, and who ends up paying the ultimate price.

Until the mortgage field services industry acknowledges this truth, Inspectors and Technicians alike will remain at the mercy of policies written by people who have never once stood on a stranger’s porch with a clipboard, wondering whether this will be the house that ends them. The solution is simple, humane, and long overdue: stop the knocks, stop the hangers, and bring back the drive-by inspection. Anything less is an invitation to tragedy.