In the balmy fall of October 2025, a LinkedIn post from analyst Tom Farwell cut through the humid air of Florida’s housing discourse like a warning flare. Farwell mapped out nearly 3,600 properties across the Sunshine State, with about 2,700 purchased in the last three years or less and all are now trapped in negative equity, where market values dip below outstanding loan balances plus closing costs. This stark visualization did not capture distant echoes from the 2008 crash but instead spotlighted fresh wounds from the post-COVID buying frenzy. These are not faceless investors gaming the system but teachers, nurses, and service workers who stretched thin on minimal down payments amid skyrocketing prices. Farwell’s data underscores a microcosm of vulnerability that ripples outward, portending a macro shift in foreclosure volumes sure to swamp the mortgage field services industry. As interest rates locked in at the six to seven percent or higher continue to bite, these recent buyers face the grim math of vanishing equity with every tick downward in home values. The canary in this coalmine chirps not from Wall Street boardrooms but from suburban driveways where families now ponder the unthinkable: default.

The precision of Farwell’s metric leaves no room for optimism, calculating only the cold arithmetic of value minus debt minus escrow fees. Seller concessions and incentives do not factor in, stripping away any illusions of wiggle room for desperate transactions. This cohort of 2,706 homes purchased between 2021 and 2023 represents a perfect storm of exuberance and entrapment. Buyers locked into high-rate mortgages watched as Federal Reserve hikes transformed affordable payments into monthly millstones. Even a modest five percent dip in local markets could wipe out their slim cushions, turning listings into liabilities. Florida’s coastal allure drew them in with promises of sun-soaked stability, yet the state’s volatile insurance premiums and hurricane risks now compound the squeeze. These homeowners are not outliers but harbingers, their plight mirroring the quiet desperation building in Sun Belt strongholds nationwide. As equity evaporates, the foreclosure pipeline thickens, demanding an army of Field Service Technicians and Inspectors to preserve and process the fallout.

Florida’s housing market, long a beacon for migration and investment, now teeters on this underwater ledge with alarming specificity. Cities like Cape Coral report 7.8 percent of mortgaged homes seriously underwater, meaning owners owe at least 25 percent more than their property’s worth. Lakeland follows at 4.4 percent, while broader state trends show seriously underwater rates climbing from 1.3 percent to 1.6 percent year-over-year. This surge defies the narrative of an unbreakable recovery, exposing cracks widened by post-pandemic inflation and supply chain snarls. Ordinary Floridians who relocated for remote work or retirement savings now confront the reality that their equity-rich dreams have soured into negative territory. The state’s second-place ranking in national foreclosure rates as of July 2025 only amplifies the urgency, with one in every 2,420 homes facing judicial action. These figures do not yet include the shadow inventory of distressed listings held off-market by fearful owners. When the dam breaks, the torrent will flood communities already strained by climate vulnerabilities and economic disparities.

Zooming out to the national canvas, Florida’s predicament sketches a portrait of America’s broader housing fragility in late 2025. ATTOM data reveals 1.15 million U.S. homes in negative equity as of the second quarter, a figure that climbed steadily by over 18 percent YOY amid persistent high rates. The share of seriously underwater mortgages nationwide holds at 2.7 percent, but hotspots in Texas and Illinois echo Florida’s woes with similar post-COVID buyer regrets. Homeowner equity slipped to 46.1 percent equity-rich properties in the third quarter, down from prior highs and signaling a reversal. This is not the subprime speculation of yesteryear but a retail-driven malaise born of FOMO-fueled purchases at inflated prices. Buyers who entered at 2021 peaks with rates under four percent refinanced little before the hikes hit, stranding them in payment shock. Delinquency rates tick upward calendar-effect driven, yet foreclosure starts rose six percent year-over-year for nine straight months. The mortgage field services sector, long dormant in the low-default era, braces for a workload resurgence that prioritizes profits over people.

The culprit in this slow-motion unraveling traces back to the interest rate vise clamped post-COVID, when central bankers battled inflation with aggressive hikes. Borrowers who signed in 2022 and 2023 committed to 30-year fixed rates averaging 6.5 to 7.5 percent, far above the sub-three percent era that fueled the boom. These elevated costs erode affordability, turning once-viable budgets into precarious ledgers where property taxes and maintenance outpace wage growth. Florida’s influx of newcomers amplified demand, but now remote work’s fade and hybrid realities leave many overextended in high-cost enclaves. A small price correction, perhaps triggered by seasonal slowdowns or insurance hikes, suffices to submerge these recent owners. For investors, though, that holy grail of CAP rate is now heading into free fall. And that free fall is serious when you contemplate the fact that they are usually all in at the 10K+ level of asset purchasing. Ethical questions arise as lenders, flush with pandemic-era forbearance buffers, eye the default wave with calculated detachment. The human toll mounts as families weigh short sales against credit ruin, unaware that their distress feeds a field services machine geared for volume over care. This rate-induced trap ensnares not speculators but strivers, whose foreclosures will demand meticulous on-the-ground responses from an underpaid workforce.

Foreclosure trends in Florida crystallize this macro pressure into actionable distress, with national filings up 17 percent year-over-year in the third quarter of 2025. Bank repossessions surged 33 percent nationally, but the Sunshine State’s 3.4 percent rise in foreclosures through July marks it second only to Illinois in per capita pain. Pre-pandemic levels loom as first-half starts approached 2022 volumes, outpacing the quiet years of forbearance extensions. High rates exacerbate this, as adjustable-rate mortgage resets and ARM hybrids trigger payment spikes for the vulnerable. Experts predict sustained climbs into 2026, with Florida’s judicial foreclosure process delaying but not deterring the inevitable. This uptick does not yet reflect the full underwater cohort, many of whom cling to payments via credit cards or side gigs until exhaustion sets in. The economic ripple hits local tax bases and school funding, as vacant properties breed blight in once-thriving neighborhoods. For the mortgage servicing ecosystem, this means a scramble to deploy inspectors and technicians, often at the expense of quality and worker safety.

The mortgage field services industry, a shadowy backbone of foreclosure management, stands poised for this influx with a mix of dread and opportunism. As underwater listings convert to notices of default, demand for occupancy verifications and condition assessments will spike, overwhelming an already fragmented contractor network. Field Service Technicians, tasked with the gritty labor of grass cutting, debris hauling, and winterization, face marathon schedules without proportional hazard pay. Inspectors, meanwhile, must navigate drive-by evaluations and photo-documentation under tight deadlines, their reports feeding algorithmic decisions that sideline human nuance. This dual workforce, distinct in roles yet united in precarity, absorbs the brunt of volume surges without union protections or standardized wages. Ethical lapses abound as national vendors outsource to local subs, diluting accountability and inflating bid undercutting. The 2025 foreclosure upswing, projected at 18 percent nationally, amplifies these strains, turning routine gigs into endurance tests. Labor-first advocates warn that without regulatory intervention, this cycle perpetuates exploitation masked as efficiency.

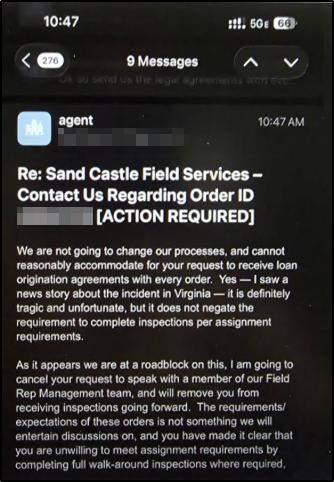

Inspectors in the field services chain bear the initial reconnaissance burden, their eyes and cameras the first line against asset deterioration. These professionals conduct drive-by occupancy checks, snapping timestamped photos of mailboxes, utilities, and curb appeal to certify vacancy or risk. In a rising foreclosure tide, their caseloads balloon, often exceeding 50 properties daily across sprawling Florida counties. Yet compensation hovers at $5 to $10 per inspection, barely covering fuel and vehicle wear in hurricane-prone zones. Legal mandates under Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac guidelines require bi-monthly verifications, but surging volumes invite shortcuts like unverified GPS stamps. Ethical dilemmas surface when inspectors, pressured by vendor portals, overlook subtle signs of owner distress in favor of binary occupied-vacant calls. This role demands not just technical skill but empathetic judgment, qualities eroded by gig-economy metrics that penalize thoroughness. As Florida’s underwater wave crests, inspectors become unwitting sentinels, their reports accelerating evictions without recourse for struggling families. The recent murder of a Field Service Technician, Michael Dodge II, adds fuel to the fire for Labor with respect to safety and compensation.

Field Service Technicians, the unsung muscle of property preservation, confront the physical aftermath with tools in hand and resolve in heart. These workers secure boarded windows, evict debris from overgrown lots, and haul away hazards that invite liability lawsuits. Distinguishing their labor from inspectors’ assessments proves crucial, as technicians execute the hands-on mitigations that prevent further value erosion. In 2025 – 2026’s foreclosure resurgence, their workloads could double, with bids structured to favor speed over safety in biohazard cleanups or lock changes. Wages stagnate at far less than $10 hourly, exposing them to uninsured risks like mold exposure or feral animal encounters and violence without overtime guarantees. Economic pressures from high rates translate here into corner-cutting, as contractors shave margins by deploying undertrained crews. Inspectors and technicians, misclassified employees labeled as independent or sub-subcontractors, lack the bargaining power to demand PPE kits or weather stipends amid Florida’s relentless storms. This labor tier, vital to the $3 billion field services market, absorbs the ethical weight of foreclosures as community caretakers turned into disposable assets.

The economic fallout for field workers in this underwater era extends beyond paychecks into precarious livelihoods that mirror homeowners’ plights. Technicians and inspectors alike juggle multiple vendor accounts, their income volatility echoing the mortgage resets that sparked the crisis. And with the latest collapse of Bishop Inspections, Labor is now, more than ever, concerned with simply being paid! Rising foreclosures promise short-term gig booms, yet historical patterns show vendors slashing rates post-peak, stranding workers in debt. Florida’s gig economy, buoyed by seasonal tourism, leaves these professionals vulnerable to off-season lulls exacerbated by default delays. Legal recourse remains elusive, as arbitration clauses in vendor agreements shield corporations from wage theft claims. Ethical imperatives demand fair labor audits, yet the industry’s opacity fosters a race to the bottom where safety certifications lapse. Communities suffer too, as preserved properties sit as eyesores, depressing neighboring values and straining municipal budgets. A labor-first reckoning calls for transparency in bid allocations, ensuring that the profits from distress flow back to those who toil in the trenches.

Legal entanglements in the field services realm intensify with every foreclosure filing, as compliance becomes the thin line between order and chaos. Technicians must adhere to state-specific preservation standards under threat of servicer penalties. Inspectors face scrutiny under FHA-HUD guidelines for accurate reporting, where falsified drive-bys invite fraud probes amid volume pressures. The 2025 uptick in judicial foreclosures prolongs property holds, multiplying inspection cycles and preservation bids without cost adjustments. Economic incentives skew toward minimal interventions, leaving technicians and inspectors exposed to civil suits from aggrieved former owners. Regulatory gaps persist, with no federal oversight on subcontractor classifications that classify full-time laborers as independents. As underwater homes tip into default, the industry must confront these liabilities head-on, prioritizing worker indemnification over expedited payouts.

Ethical shadows lengthen over the mortgage field services landscape as profit motives clash with human costs in Florida’s brewing storm. Vendors, chasing lucrative REO contracts, often prioritize algorithmic efficiency over holistic preservation that honors community fabric. Technicians and inspectors, directed to clear personal effects without sensitivity, become complicit in the dehumanizing grind of eviction. Inspectors’ condition reports, rushed for portal uploads, gloss over repairable issues that could avert full foreclosures. The post-COVID rate hike’s victims, these recent buyers, deserve interventions like loss mitigation counseling, yet field workers see only the endpoint of neglect. Labor exploitation compounds this, as technicians and inspectors endure wage docking for incomplete gigs in hurricane aftermaths, years after the events. A true reckoning demands stakeholder accountability, from GSEs to ground crews, fostering partnerships that value equity in process. Without such shifts, the underwater crisis risks drowning not just homes but the moral core of an industry built on recovery.

In the end, Tom Farwell’s map serves as more than data points, it illuminates a pathway for reform in the mortgage field services arena. Policymakers must mandate living wages and training mandates for technicians and inspectors, decoupling their fates from foreclosure volatility. Economic models should incorporate community impact assessments, ensuring preservation work rebuilds rather than ravages neighborhoods. Legal frameworks need strengthening to penalize vendor non-compliance, protecting workers from the fallout of high-rate regrets. Ethical training programs could empower field personnel to flag distress early, bridging the gap between assessment and aid. Florida’s underwater undercurrent, if harnessed wisely, could catalyze a labor-first evolution in this vital sector. Homeowners adrift in negative equity deserve dignity, and the workers who preserve their legacies merit respect. As 2025 wanes, the choice looms: perpetuate the cycle of extraction or chart a course toward sustainable stewardship. The coalmine echoes with urgency, but the canary’s song still holds notes of hope.