As if the latest workplace execution of an underpaid and employee misclassified Field Service Technician wasn’t enough, Sand Castle Field Services chose to sully the name of the victim and circumstances surrounding the horrific event. From the beginning, NAMFS Executive Director Eric Miller attempted to spin the tale that Michael Dodge II was an “employee” as per Miller’s 23 October 2025 email to National Association of Field Services (NAMFS) members. A simple phone call or Google search would have revealed this was ANYTHING but the truth. In the dim predawn hours of October 21, 2025, Michael Dodge II drove his truck to a nondescript single-family home on the 600 block of Mountain View Road in Stafford County, Virginia. He was there not as an intruder, but as a Field Service Technician dispatched by layers of subcontractors in the mortgage field services industry to secure a property presumed vacant after foreclosure proceedings had begun. Armed only with a toolkit of locksets, drills, and a clipboard of digital orders, the 35-year-old father from Caroline County stepped out into the chill, expecting the routine hazards of overgrown weeds or scattered debris, not the barrel of a loaded firearm. What unfolded next was no mere “incident,” as euphemistically labeled in the terse text and emails circulating among order mills, including Sand Castle, but a cold-blooded murder that exposed the rotting underbelly of an industry built on the backs of disposable labor. Deputies from the Stafford County Sheriff’s Office arrived to find Dodge unresponsive, multiple gunshot wounds riddling his body, his blood pooling on the asphalt like an accusation against the system that sent him there alone. The shooter, 64-year-old Donald Thomas, a resident who had apparently refused to vacate despite eviction notices, was arrested hours later on first-degree murder charges, his motive rooted in a desperate stand against the impersonal machinery of asset recovery. Yet, even as Dodge’s family grappled with unimaginable grief—his mother wailing, “You killed my son for nothing“—the industry’s response trickled out in sanitized memos, reclassifying a homicide as a bureaucratic snag, an requiring no deeper reckoning. This whitewashing, evident in the automated alerts from firms like Sand Castle that halted “processes” without acknowledging the human cost, reveals a profound ethical rot, where profit margins eclipse the lives of those who literally turn the keys on America’s discarded dreams.

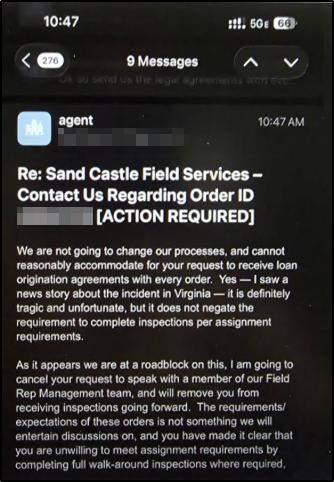

The text from Sand Castle Field Services, timestamped at 10:47 AM, landed in box of an inspector requesting more information on assets with the clinical detachment of a weather report. “Re: Sand Castle Field Services – Contact Us Regarding Order ID [ACTION REQUIRED],” it began, before pivoting to the heart of the matter: an “incident” in Virginia and that regrettably precluded accommodating a routine loan origination info about the other properties in question. Nowhere in its 150 words did it utter Dodge’s name, describe the hail of bullets, or confront the fact that this was a Field Service Technician—distinct from the drive-by Inspectors who snap photos from afar—executed while performing the gritty labor of lock changes and securing. Field Service Technicians like Dodge wade into the fray of physical preservation, spending hours wrestling with rusted hinges, hauling away biohazardous waste, and braving structural collapses, all for per-task reimbursements that barely cover gas and gear. Inspectors, by contrast, orbit these sites in relative safety, logging occupancy checks or condition reports in under ten minutes via apps, their risks confined to misjudged drive-bys rather than boots-on-ground confrontations. Sand Castle’s missive, with its passive voice and bracketed urgency, wasn’t born of malice alone but of a systemic allergy to accountability, where labeling a murder an “incident” allows vendors to pause workflows without triggering the legal or reputational earthquakes that might force higher bids or safety mandates. Economically, this sleight of hand preserves the razor-thin margins servicers demand, passing the peril downstream to underinsured contractors who foot the bill in blood and trauma. Ethically, it dehumanizes Dodge from a dedicated provider—father to young children, pillar to his community—into an interchangeable line item, a “roadblock” to be cleared en route to the next assignment. Legally, such obfuscation skirts workers’ compensation claims, OSHA inquiries, and potential negligence suits against the mortgage giants who outsource their dirty work through opaque subcontractor chains.

As news of the shooting rippled through the tight-knit circles of Field Service Technicians, the Foreclosurepedia Nation quickly mobilized with the fury of those long accustomed to being gaslit by corporate overlords. Posts on industry forums and private X threads dissected the Sand Castle text, highlighting its dangerous precedent: if a point-blank execution merits only an “incident” tag, what hope exists for the everyday perils of hypodermic needles in lawns or feral dogs guarding squatter dens? Michael Dodge II wasn’t some abstract statistic; he was a linchpin in the mortgage asset chain, tasked that fateful morning with rekeying a door to prevent further decay on a property foreclosed upon by a servicer whose name remains shrouded in nondisclosure agreements. His coworker, listening helplessly over the phone as shots rang out, became an unwitting witness to the industry’s failure to equip its technicians with even basic redundancies like duress alarms or paired-site protocols. In the hours after, as Stafford deputies cordoned off the scene with yellow tape fluttering like foreclosure notices, Dodge’s parents arrived not to a hero’s vigil but to a void of support from the vendor ecosystem that employed him. The economic implication here is stark: Field Service Technicians earn a fraction of what their labor merits—often $25 to $50 per lockout, minus tool costs and travel—while Inspectors pocket $15 for a photo upload, perpetuating a caste system that undervalues the very hands that maintain portfolio values. Legally, the ambiguity of Dodge’s status—1099 contractor or W-2 employee—looms large, with NAMFS Executive Director Eric Miller’s offhand “employee” reference in media statements clashing against the gig-economy reality that denies benefits like life insurance. Ethically, this murder demands a moratorium on solo assignments to high-risk REO properties, yet Sand Castle’s whitewash suggests vendors will instead accelerate the churn, dispatching the next technician before the concrete dries on Dodge’s memorial.

Delving deeper into the mechanics of this whitewashing reveals a playbook honed over decades of post-2008 austerity, where mortgage servicers squeeze vendors until the only variable left to cut is human safety. Sand Castle Field Services, a mid-tier order mill in the preservation subcontracting game, operates in the gray zone between national aggregators and local boots-on-ground operators, routing orders through apps that prioritize speed over scrutiny. Their text’s invocation of a “definitive tragic and unfortunate incident” isn’t isolated; it’s echoed in countless vendor alerts that reframe assaults as “occupant resistance” or fatalities as “unforeseen events,” shielding upstream Clients from the fallout. For Field Service Technicians, this means entering war zones disguised as suburbs—vacant homes colonized by holdouts like Thomas, whose armed defiance stemmed from the same eviction pipeline Dodge was paid to enforce. Inspectors, mercifully, rarely cross this threshold; their role ends at the curb, uploading geotagged images that trigger the technician’s descent into the breach. Economically, the whitewash sustains a race to the bottom, with bids plummeting as vendors absorb risks without premium pricing, leaving families like Dodge’s to crowdsource funerals via GoFundMe while CEOs toast quarterly efficiencies. Legally, it invites scrutiny under Virginia’s workplace violence statutes, where if there was failure to assess site-specific threats—such as ignored prior complaints about the Mountain View property—could cascade into class-action territory for misclassification and negligence. Ethically, the industry’s silence on Dodge’s behalf indicts a culture that views labor as expendable, a sentiment crystallized when NAMFS issued a perfunctory statement urging “prayers” without pledging fund earmarks for safety tech like the NFC-embedded ID cards pioneered by the International Association of Field Service Technicians (IAFST).

The broader canvas of the mortgage field services industry paints Dodge’s death not as anomaly but archetype, a flare-up in a powder keg of under-regulation and over-exploitation that has simmered since the Great Recession. Thousands of properties nationwide sit in limbo, their former owners displaced by algorithmic foreclosures, only to become tinderboxes for the technicians dispatched to board them up. Field Service Technicians bear the brunt, their days a gauntlet of winterizations gone awry in subzero temps or debris hauls uncovering asbestos-laced nightmares, all while earning wages that trap them in perpetual precarity. Inspectors, siloed in their observational silos, contribute data points that fuel this cycle but evade the visceral toll, their reports often the spark that ignites a preservation order. Sand Castle’s text, by downplaying the murder as an “incident,” exemplifies how vendors launder liability, notifying only those orders directly impacted while burying the systemic critique in fine print. Economically, this perpetuates wage suppression; without a dedicated NAICS code for field services—as petitioned for by IAFST—the labor pool remains fragmented, ripe for exploitation by servicers who cap reimbursements at 2010 levels despite inflation’s bite. Legally, the implications ripple to federal levels, with OSHA’s general duty clause potentially ensnaring non-compliant firms in fines, and wrongful death suits probing the subcontractor daisy chain for breaches in duty of care. Ethically, it forces a reckoning: how can an industry that profits from human ruin send its workers into the fray unequipped, then memorialize them with platitudes rather than policy?

As Dodge’s body was wheeled away under flashing lights, the vacuum of official response from his presumed employer—a faceless mortgage servicer yet to make a statement—spoke volumes about the power imbalances baked into every work order. Technicians like him operate in a shadow economy, their 1099 forms a shield for vendors against liability, yet a sword when claims arise for injury or loss. The text’s casual pivot to “full walk-around inspections where required” underscores this disconnect: while Inspectors might suffice for cursory checks, the murder halted deeper engagements, not out of respect for the dead but to evade the optics of vulnerability. Field Service Technicians demand more—paired crews for lockouts, real-time GPS pings to dispatch, and contractual clauses mandating risk disclosures—yet vendors like Sand Castle prioritize throughput, whitewashing disruptions to keep the pipeline flowing. Economically, the murder exposes the false economy of low-bid wins; a single fatality’s ripple—lost productivity, legal fees, morale craters—dwarfs the pennies saved on safety. Legally, Virginia’s courts could soon test precedents, with Dodge’s estate likely pursuing discovery into assignment protocols, revealing if prior intel on Thomas’s occupancy was suppressed to cut corners. Ethically, the whitewash erodes trust, turning colleagues into wary lone wolves who second-guess every ding on their app, wondering if today’s “vacant” is tomorrow’s ambush.

Industry veterans, those grizzled Field Service Technicians who’ve dodged their own brushes with violence from indignant holdouts or opportunistic thieves, view Dodge’s story through lenses cracked by cumulative trauma. They’ve long whispered of properties flagged as low-risk only to reveal armed squatters or booby-trapped entries, yet vendor dashboards rarely reflect these ground truths, prioritizing algorithmic efficiency over anecdotal wisdom. Sand Castle’s framing as an “incident” dismisses this oral history, reducing Dodge to a data glitch rather than a cautionary tale demanding protocol overhauls. Inspectors, feeding the beast with their snapshots, unwittingly amplify these mismatches, their reports lacking the nuance of a technician’s sweat-soaked assessment. Economically, the push for arming workers—now gaining traction in vendor huddles—signals desperation, as concealed carry premiums outpace investments in de-escalation training or community liaison roles. Legally, such measures invite a minefield of Second Amendment clashes with servicer policies, potentially voiding insurance while exposing workers to escalated force. Ethically, it flips the script from prevention to reaction, absolving the industry of its role in fostering confrontations through opaque eviction mills.

The International Association of Field Service Technicians (IAFST), ever the bulwark for the boots-on-ground, issued a blistering rebuke to Sand Castle’s euphemism, calling for mandatory incident debriefs that name victims and dissect failures—the administrative autopsy. Their NFC cards, designed for quick-scan verification to humanize encounters, could have bought Dodge precious seconds in that driveway, a polite “I’m here to help secure the home” projected via app before the trigger pull. Yet, adoption lags, as cost-conscious vendors balk at anything beyond bare-minimum bids. Field Service Technicians rally around IAFST’s university platform, seeking certifications that elevate their craft beyond grunt work, but Inspectors—often siloed in separate certification tracks—miss this camaraderie, their isolation breeding apathy toward the downstream dangers. Economically, a NAICS code would unlock federal grants for safety gear, leveling the field against Inspectors’ lighter loads. Legally, it would clarify jurisdiction, pulling technicians from gig limbo into protected classes eligible for comp claims. Ethically, honoring Dodge means embedding his memory in every order form, a perpetual reminder that whitewashing erases not just facts, but futures.

As Stafford County processes Thomas’s charges, the mortgage field’s complicity simmers unspoken, with Sand Castle’s text a microcosm of how vendors inoculate themselves against outrage. No press release mourned Dodge; instead, rerouted orders flooded inboxes, the murder mere static in the signal. Field Service Technicians, versed in this resilience, share war stories of near-misses—a knife-wielding evictee in Ohio, a pit bull lunge in Florida—fueling underground networks that bypass official channels for real talk. Inspectors, peering from afar, contribute less to this lore, their detachment a privilege the industry exploits to keep costs compartmentalized. Economically, the whitewash sustains a multi-billion dollar sector where labor claims a sliver, technicians subsidized by second jobs while executives yacht on portfolio proceeds. Legally, emerging suits could mandate audit trails for risk assessments, forcing transparency on “vacant” designations that proved fatal for Dodge. Ethically, it begs: when does an “incident” become indictment, and who pays the moral debt?

Foreclosurepedia and the IAFST stand together with the Dodges and every technician who’s stared down a shadowed doorway, demanding the mortgage machine grind to a halt until it learns to value lives over liens. The whitewash ends here, in ink and outrage, as we catalog the costs not in dollars but in the empty chairs at family tables. Field Service Technicians aren’t pawns; they’re the unseen architects of recovery, deserving fortresses of support, not flimsy euphemisms. Inspectors, witnesses to the prelude, must amplify these calls, bridging the gulf that isolates us all. Economically, justice means wages that reflect risk, not relics of recession. Legally, it means chains of custody for every order, tracing bullets back to boardrooms. Ethically, Michael Dodge II’s legacy will be the mirror we force upon this industry, reflecting not glory, but the gore we’ve long averted our eyes from.

This murder, far from an isolated “incident,” threads into a tapestry of tragedies that the field services world can no longer afford to fringe. Sand Castle’s text, archived now in legal folios, will serve as exhibit A in the court of public opinion, where vendors learn that whitewashing washes away nothing but their own credibility. Field Service Technicians gear up for the long haul, their toolbelts heavier with resolve, demanding IAFST-backed reforms that arm them with policy as much as pliers. Inspectors, too, stand to gain from unified fronts, their reports evolving to flag not just vacancy but volatility. Economically, the tide turns with collective bargaining, wresting control from aggregators who treat humans as hyperlinks. Legally, precedents like Dodge’s could birth a Field Services Bill of Rights, codifying protections long deferred. Ethically, we owe him truth: a workplace execution, not an incident, born of an industry’s indifference to the doors it dares its workers to knock on.